The Value Illusion (Delusion)

Or: Why What Costs More Rarely Gives You More — and What We Owe to the Word “Value”

There are few words in the modern consumer lexicon more abused than value.

We invoke it when describing a bargain. (“Great value for money.”) We weaponise it in luxury marketing. (“Our pieces are an investment.”) We deploy it in sustainability discourse, like a protective spell meant to ward off questions of overconsumption. (“We believe in timeless value, not trend.”)

But ask ten brands what the word means — and you’ll get eleven answers. Usually involving the phrase “premium” and very rarely involving, say, labour conditions or tensile strength.

This, of course, is no accident. It is not an oversight. It is the system.

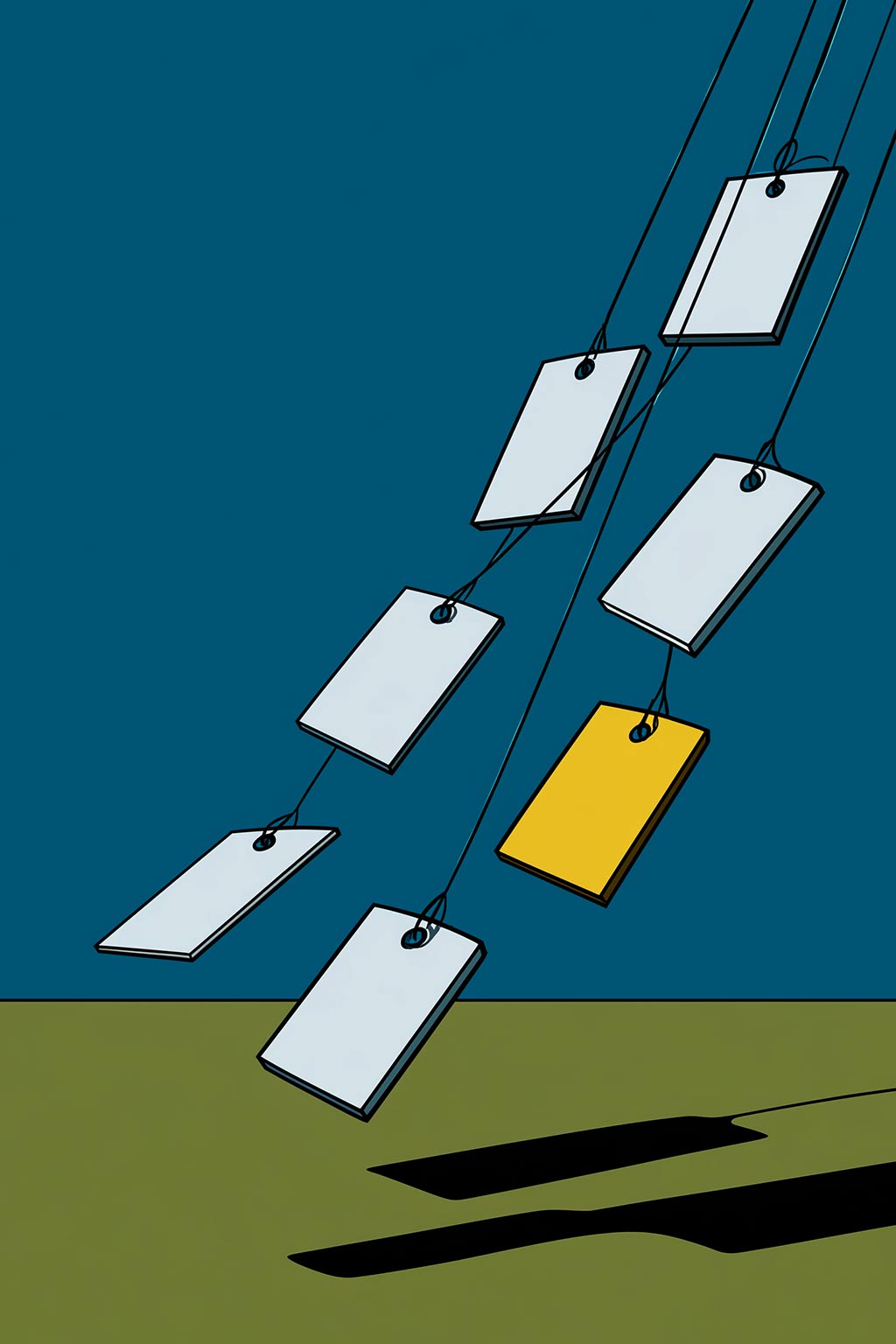

Value has become the most flexible lie in fashion’s vocabulary.

It can mean cheap, expensive, recyclable, exclusive, or enduring. It is used to justify mass production as readily as it is used to frame a minimalist knit as luxury. Its power lies in its deliberate ambiguity — and the broader the term, the greater the markup.

The Price Tag Illusion

(aka: If it costs more, it must be better. Right?)

Let us begin with the most enduring fallacy in retail: the conflation of price with worth.

In fast fashion, "value" is equated with quantity and convenience. The £12 jumper. The three-for-two basics. The dopamine rush of checkout total math so low it feels fictional. Quantity becomes its own logic. If one t-shirt is £6, then ten must be ten times as good. Never mind the fibre content. Or the stitch count. Or the human cost. Harmful to both people and planet.

At the other end of the spectrum, luxury fashion performs the inverse trick: less for more. A t-shirt priced at £300, with no visible branding and no material difference from its high street cousin, is presented as an "investment piece." A near-empty bottle of “scented water” for £160.

Here, value is manufactured through scarcity, moodboard minimalism, and the performance of taste. Price becomes its own product.

In both cases, the consumer is being played. The trick is simple. One side flatters your thrift. The other flatters your taste. Neither guarantees a better product.

Both profit from your confusion.